• Official Development Assistance (ODA) refers to financial assistance provided to developing countries and the multilateral

institutions by official agencies, including state and local governments of developed countries for promotion of their economic

development and welfare. In 1970, it was agreed that developed countries would provide 0.7 per cent of their Gross National Income

(GNI) as ODA to developing countries. ODA is also known as foreign aid.”

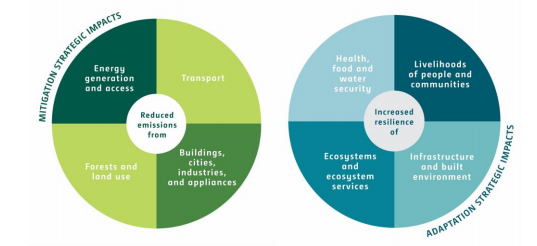

• Climate finance. The 2016 Biennial Assessment and Overview of Climate Finance Flows (UNFCCC), refers to climate

finance as financial resources dedicated to adapting and mitigating climate change globally, aiming at reducing GFG emissions,

reducing vulnerability, and maintaining and increasing the resilience of human and ecological systems to the negative climate change impacts.

• Climate Public Expenditure and Institutional Review. (CPEIR) is a methodological tool to analyze, how climate change related

expenditure is being integrated into national and sub-national budgetary processes. It has three key pillars: Policy Analysis,

Institutional Analysis and Climate Public Expenditure Analysis. It supports to identify and track climate related expenditure

in the national budget.

• Co-financing refers to conditions that recipient entities need to fulfil to receive financial support from funds.

These conditions may include earmarking funds to certain sectors, co-financing, procurement design, fulfilling certain

criteria under social and environmental context, etc.

• Conditionality refers to conditions that recipient entities need to fulfil to receive financial support

from funds. These conditions may include earmarking funds to certain sectors, co-financing, procurement design, fulfilling certain

criteria under social and environmental context, etc.

• Leverage is used in the context of climate finance in which it refers to public finance (e.g. from international

finance institutions) that is used to encourage private investors to back the same project. This can be in the form of loans,

risk guarantees and insurance or private equity. This is also intended to reduce the perceived risk for the private sector.

Financial institutions apply the terminology ‘leveraging’ to understand how their core contributions (for example, money

provided by donor governments to a multilateral development bank) can be invested in capital markets to create an internal

multiplier effect.

• On-lending. An entity accredited under specialized fiduciary standards can receive money from a fund with

the intention of lending it to other executing entities for the implementation of selected programmes and/or projects.

This can also include providing equity or guarantees to other entities.

• Project Preparation Facility (PPF) is used as means of developing bankable, investment-ready projects.

A PPF may provide both technical and/or financial support to project owners/concessionaires. Such supports can cover a wide range

of activities including: undertaking project feasibility studies including value for money analysis; developing procurement documents

and project concessional agreements; undertaking social and environmental studies; and creating awareness among the stakeholders.

• Technical assistance is non-financial assistance provided by local or international specialists.

It can take the form of sharing information and expertise, instruction, skills training, transmission of working knowledge,

and consulting services and may also involve the transfer of technical data.